The future of the UK’s public service broadcasters

(Source)

Last month, we looked at Channel 4’s move away from London, and listed the cities vying to host two creative hubs and the broadcaster’s new national HQ.

Channel 4 came under pressure from the Department for Culture, Media and Sport because, according to The Telegraph, “it [the move] is likely to be viewed as a boost to the creative industries in Labour heartlands in the Midlands and North”.

The BBC is also looking at shifting some of its production out of the capital.

The corporation’s director-general, Tony Hall, said that rules controlling UK media need to change if British TV is to compete with Netflix, Amazon and YouTube.

And, speaking at the Royal Television Society, Lord Hall argued that UK's media industry is competing against global giants with “one hand tied behind its back”.

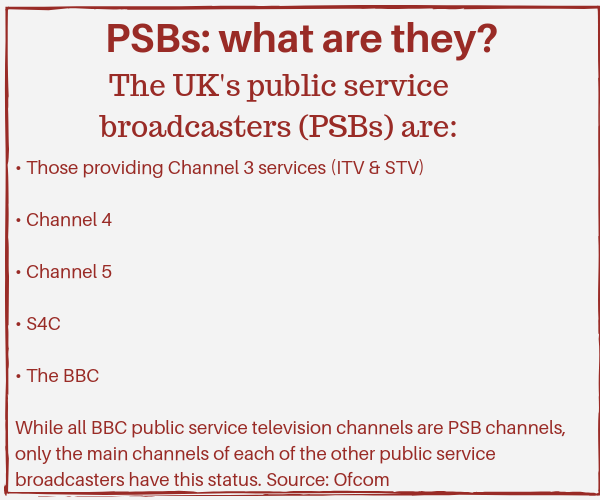

Netflix and Amazon invest £13 billion a year on content, and Britain's public service broadcasters (PSBs) are losing younger viewers to those huge OTT services.

So, what does Lord Hall suggest for the BBC?

- Make the iPlayer a “destination” rather than merely a catch-up service

- Spend more on youth programming and the highest quality output

- Shift more production out of London to the rest of the UK

But are those measures really going to make a difference? It’s clear that the BBC has at least two massive challenges:

- How can it attract and retain younger viewers, ie those in their teens and 20s, if spending more on youth programming doesn’t work?

- What if moving production out of London doesn’t make a difference?

And what if those two problems aren’t in fact connected?

Outdated business model?

It could be argued that the BBC’s business model is out of date and similar to that of a high street bank, particularly in the pre-digital age: attract customers when they’re young and somehow manage to hold on to them for the rest of their lives.

Will investing in CBeebies and CBBC really keep young viewers watching BBC TV and away from Netflix, Amazon and YouTube?

And what about all that time and attention young people devote to Instagram, Snapchat, Facebook, musical.ly/TikTok, Twitter and the rest?

The BBC is learning the hard way – and in no way is it the first major media organisation to do so – that attention and loyalty are not the same today as they were 30 years ago.

Jeremy Corbyn has his own ideas for the future of British media...

Jeremy Corbyn used his Alternative MacTaggart lecture at the Edinburgh Television Festival last month to outline his vision:

The Labour leader:

- Proposed a new tax on tech firms such as Facebook, Google and Netflix to subsidise the BBC licence fee and help fund public interest journalism

- Called for reform of the BBC, with licence fee-payers electing board representatives and a requirement for the corporation to publish data about the social classes of its staff

- Criticised large tech companies that “extract huge wealth from our shared digital space”

A future Labour government might also put the BBC on a permanent statutory footing “to end government involvement through the renewal of the broadcaster’s royal charter”.

ITV

ITV chairman Sir Peter Bazalgette said in a speech to The Voice of the Listener and Viewer Autumn Conference in November 2017:

NBC/Universal + Snap, Inc = light at the end of the tunnel?

As we wrote in April 2018, there are some success stories among traditional, linear broadcasters from which others can draw encouragement and learn.

For example, NBCU and UKTV have bold strategies that are paying off:

NBCU is an investor in Snapchat and is also the social network’s biggest producer of shows.

UKTV, meanwhile, has doubled revenues in the past seven years, partly because it’s moved away from a heavy reliance on archive BBC shows and carriage fees.

Project Kangaroo

Project Kangaroo, the video-on-demand service from the BBC, ITV and Channel 4 that never got going.

Then along came Netflix (2012) and Amazon Prime Video (2014), and now the BBC, ITV and Channel 4 are in talks again to create a new streaming service, years after the Competition Commission’s decision, which has since been described by Sir Peter Bazalgette as a “terrible, ignorant mistake”.

But...

An interesting twist in the story

News came recently that the BBC and Discovery are understood to be in the final stages of agreeing a £1 billion breakup of UKTV in a deal that “will accelerate plans to build a British streaming rival to Netflix”.

Government support

Jeremy Wright, the Secretary of State for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport, confirmed this week (18 September 2018) that the government will support the UK’s PSBs to ensure they continue to thrive and stay prominent.

Given this insight, maybe Lord Hall should listen, and consider this:

A new direction for PSBs

One thing PSBs do have is trust, as Ofcom’s 2017 annual report tells us.

But maybe PSBs should be looking in a new direction to build on that trust and reach.

The NBCU/Snap initiative shows the way forward.

Perhaps PSBs should take it a step further and look at investing in companies who manage the relationship between influencers/creators, brands and young audiences.

Ultimately, young people will spend their time in front of content they’ve largely been exposed to by friends, family members, influencers and algorithms.

The BBC, in particular, must better understand the influence on young people of influencers; it must get to grips with the power of algorithms, AI and machine learning; and it must recognise the need to invest in other areas of production – not geographically, but in terms of content.

As Sir Peter Bazalgette says: “We can’t dis-invent the internet age.”

Content

Unless the PSBs start thinking about a better commercial solution on a global scale they’ll never have the clout to compete with the tech monsters.

To attract and retain viewers of any demographic requires one thing more than any other: great content.

The PSBs’ relationship with programming is central to the whole debate. As things stand, it feels like all the best UK shows get sold off for international distribution with other providers.

Audiences go where the content is, and the BBC can’t seem to retain their biggest hitters.

Take Bodyguard, for example. One of the Beeb’s strongest originals this year, it was watched by the highest launch audience for any new drama across all UK channels in a decade. It’s already been snapped up for distribution outside the UK and Ireland by Netflix.

That follows a long line of shows that have been taken up by an overseas player: Top Gear, Poldark and The Last Kingdom, to name a few. It’d be no surprise to see Killing Eve follow suit.

If PSBs in the UK want new, improved results, is it time for new, younger leadership and bigger, bolder ambitions?

For more information, Ofcom’s report, Public service broadcasting in the digital age, dated 8 March 2018, is here.

Netflix, Paramount and Warner Bros.: What the Deal Means for the Broadcast and Production Industry

How the Employment Rights Act 2025 Is Reshaping the Freelance Market